The worst nuclear disaster in history, the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear plant meltdown, occurred because Soviet officials were certain the conditions that caused the explosion were impossible even though the exact same thing (something called Xenon poisoning) had taken place in 1983 at the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant in Lithuania, a plant with the same RBMK reactor design as Chernobyl. The disaster happened during a safety test, ironically, where the staff conducting the test was woefully untrained. Soviet officials were so positive that a nuclear meltdown could not have occurred that evacuation did not begin until a full day and a half after the explosion.

The Great Famine, which killed anywhere from 15 million to 55 million people in China between 1956 and 1961, was the result of a population explosion of pest insects and subsequent massive loss of crops, because Mao Zedong ordered the Chinese people to eradicate voracious insect-eating sparrows, which he considered to be one of the four “great pests.”

The Titanic only carried 20 lifeboats, though it had capacity for 64 that could have saved an additional 3,547 people, because the engineers believed it to be unsinkable.

The Challenger shuttle exploded because NASA ignored warnings about seals on the solid-rocket boosters at low temperatures.

Early continued reliance on ventilators to treat patients hospitalized with covid might have led to an increase in deaths by as much as 70 percent.

Both the dot com crash and the global financial crisis of the late 2000s were largely because of people’s belief that they could never occur.

The list of mistakes, crashes, disasters, death, suffering, and destruction driven by humanity’s propensity for myopic thinking and allegiance to a narrative over a willingness to embrace fact and nuance is as long as human history itself. Not long ago, the United States, and the entire financial world, held its collective breath in fear as Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the sixteenth largest bank in the U.S., failed, followed by others, with predictions for even more dominating financial headlines.

In the wake of catastrophes like the one at SVB, it’s easy to say that trained professionals should have seen it coming, though predictions like that tend to be simpler in hindsight. What is more predictable, unfortunately, is the backlash of finger pointing and politicians from both sides of the aisle trying to capitalize on the latest crisis to score political points.

SVB CEO Greg Becker served on the board at the San Francisco Federal Reserve, the entity that was supposed to provide oversight of his bank. Two days before SVB failed, Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell’s assured congress that raising rates presented no danger to the economy. And yet we are being told by some politicians that SVB failed because its leadership was overly focused on the new boogieman, “ESG.”

While the factors that led to the second largest bank failure in U.S. history are almost certainly more complex than the political ideology of its leadership, it remains possible that a myopic, rigid adherence to that ideology took focus away from executives who should have been paying more attention to the expanding risk caused by the company’s portfolio concentration.

Those same people making accusations that SVB failed because of its executives’ political leanings have adopted the same singular stance in opposing anything with the letters “E,” “S,” and “G” attached to it, the same absolutist posturing taken by proponents of the immediate elimination of fossil fuels. It’s almost as if everyone who has a stake in the direction of the popular narrative – politicians, corporates, lobbyists, and legacy media, for example – is interested in promulgating a viewpoint that benefits them with no regard for accuracy, nuance, and negative impacts.

The backlash against ESG has been building for years, and SVB is by no means the first instance of seemingly misplaced blame with ESG as the villain, just the latest. The intensity of the blowback feels like it has increased recently, not just in volume, but in action. Congressional Republicans passed a bill that would reverse Biden’s ESG investment executive order, which Biden promptly made his first veto. Florida and Texas are the two most high-profile of the now-19 states that have passed some form of anti-ESG legislation. Companies that have earnestly adopted sustainability initiatives as part of a long-term strategy face scorn and calls for boycotts and bans.

Not that myopic thinking and lack of nuance is reserved for one side. Nuclear power has withered under the pressure of fear campaigns even though more than ten times as many people die annually from coal and oil accidents than the total number of deaths from nuclear ever. Wind and solar are inefficient, subject to the whims of the wind and sun, and have a host of problems. Wind turbines, in particular, are devastating to birds, and is now proving to be a direct cause of significant increase in the deaths of whales and other sonar-guided animals. Abandoning fossil fuels in favor of these “green” sources of energy threatened significant human misery in Europe this winter, with coal the savior.

Hidden amidst all of this is the hypocrisy of bad faith actors who publicly tout ESG-related strategies while embracing practices that run utterly counter to what they promote. Greenwashing is a recent buzzword because it is a very real concern, with public outcry, regulatory scrutiny, and even penalties as a consequence. Companies that claim to embrace DEI on paper do the opposite in reality when they think they can get away with it.

ESG does not have to be a boogeyman, nor does it have to be an iron rod driving extreme behaviors in pursuit of nebulous goals. No matter what someone’s stance is on the best way to improve our world, the term “ESG” should not be a political tool to ignore the negative consequences of whatever position that person is promoting.

At its core, ESG means taking all factors into account as part of a long-term strategy. It means considering the impact on the larger world in each decision. It is a far less controversial topic among the actual American public than most popular news programs would have us believe, with Republicans, Democrats, Independents, and all others having fairly similar viewpoints on the need to be good stewards of our environment and work for a society that is more beneficial to more people, even as we disagree on the best way to get there.

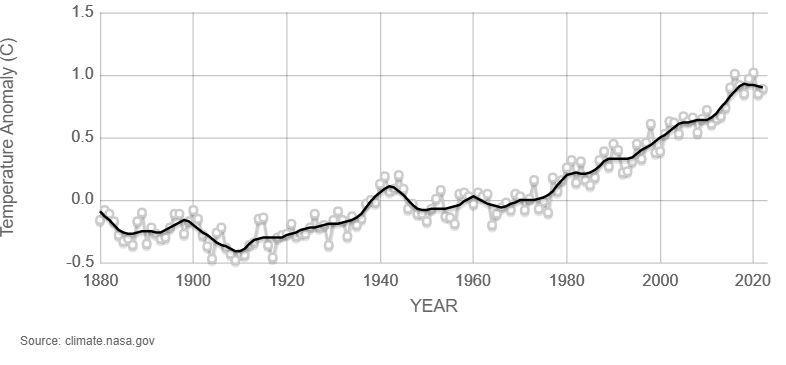

It isn’t surprising that people take this seriously, as the symptoms of our impact on the world are increasingly apparent. The planet is increasing in temperature and the correlation with increasing atmospheric carbon ppm is clear. This shouldn’t be surprising; it gets colder higher up a mountain because the air is thinner. Climate change operates under the same basic principle.

Further, there is a plastic patch in the ocean bigger than the state of Texas, and microplastics are now found everywhere on earth. Water is one of the most abundant resources on earth, but poor water management is leading to scarcity in many places and significant populations dealing with lack of clean, safe water sources.

Biodiversity is decreasing at an alarming rate, and the impact on humankind is immeasurable. We are losing potential sources for new medicines, threatening complex food chains that ultimately allow us to grow crops which are dependent on pollinators like honeybees. Looking back in 60 years, we do not want to find that a focus on political victories has turned us into history’s latest iteration of Mao Zedong.

But ESG also demands a human-centered approach. This means that outrageous and unscientific goals that exclude all fossil fuels and result in economic disaster and people freezing to death must be challenged and debates held in good faith. Reaching a broad population and having a workforce that is representative of the American public is meritorious in advancing humanity and also leads to demonstrable financial gains, but superficial diversity prioritized over company success benefits no one and gives fodder to the naysayers.

Actions have consequences, and denial of that is a formula for failure. SVB learned that in the worst way, and the entire world will likely have to bear at least some of the burden of those consequences. Just like the Soviets, and Mao, and the engineers for the Titanic, and so many others, myopic, rigid adherence to a narrative has never turned out positive for the people who do it, and we, the people, suffer as a result.

We now have an opportunity to do some meaningful things that can serve humanity and this planet for generations to come. It seems as if we are more interested in attacking people for their beliefs to score political points than we are in engaging in sincere discussion and disagreeing productively, politics aside. Amidst a cacophony of negative voices, we need only ignore them, and they lose all their power over us. Let’s stop politicizing ESG, before we add it to our list of historical regrets.